Energy intelligence group Wood Mackenzie has published a report listing several key trends shaping the future of the energy sector, including three that are relevant to the offshore industry – the fast pace of China’s energy transition, a comparison of liquefied natural gas (LNG) and carbon capture and storage (CCS) capacity, and the potential of offshore wind compared to oil and gas in the North Sea.

Judy platform (for illustration purposes only); Source: Harbour Energy

Judy platform (for illustration purposes only); Source: Harbour Energy

As the new year rolls in, people tend to make plans and to-do lists and visualize their goals to see what the future might hold. The energy arena is no different – it is a time to take stock of the situation and assess options to secure an optimal future for our planet and its people with fresh eyes, taking in the lessons learned over the past year and major global events such as the 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) held in November.

Since the energy landscape is rapidly transforming due to decarbonization, electrification, and geopolitical shifts, Wood Mackenzie has provided some insight into the complex dynamics of energy markets. The charts in the report titled ‘Conversation Starters: Five Energy Charts to Get You Talking’ offer a visual representation of what the future of several aspects of the energy transition might bring.

The report focuses on matters such as the electrification of the automotive sector in China, where a decline in the internal combustion engine (ICE) and the rise in electric vehicle (EV) sales has been registered over the past years, and power demand growth in the United States – which the author Malcolm Forbes-Cable sees as a manifestation of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Additionally, the report highlights three notions relevant to the offshore energy sector, relating to CCS, the North Sea’s future, and the energy transition in China.

CCS’ potential

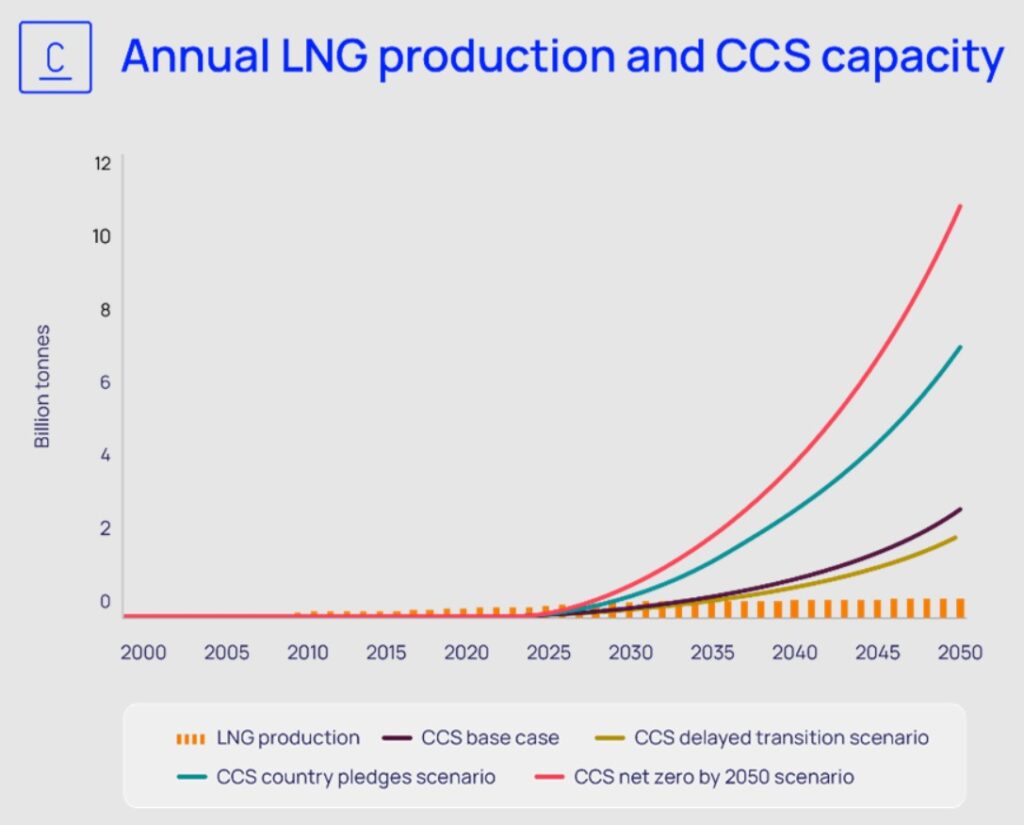

Wood Mackenzie wanted to shed some light on the scale of the global CCS industry ambition by using what the author says is a “strange” juxtaposition between LNG and CCS capacity, even though one is in the business of energy provision and the other of waste disposal.

LNG and CCS have some similarities – both entail delivering gas in a cooled liquid state from production to end market and require a large global infrastructure network for collection, processing, and transportation. The main differences are that one starts at the reservoir and delivers to the customer, the other the reverse, and that the former can be profitable, while the latter is dependent on material subsidies. Tthe author says this is unsustainable in the long run, or at least until the carbon price supports a commercial market.

When it comes to CCS, the UK government recently disclosed its plans to spend £21.7 billion on establishing two major carbon capture and storage (CCUS) clusters over the next 25 years, alongside hydrogen production facilities, in Teesside and Merseyside.

As stated in the report, LNG capacity is expected to see more than 200 million metric tonnes per annum (mmtpa) brought to market this decade at an annual growth rate of 5%. In the CCS base case between 2030 and 2050, once the industry has established itself more firmly, the annual growth rate is anticipated to reach 13% – a rate that the author says LNG has rarely matched.

“Even in the delayed energy transition scenario, CCS capacity is expected to be three times greater than LNG supply volumes by 2050, while in the base case, it will be four times greater. This will require impressive growth rates!” noted Forbes-Cable.

Source: Wood Mackenzie Lens

Source: Wood Mackenzie Lens

When discussing CCS’ potential during this year’s Offshore Energy Exhibition and Conference, industry stakeholders pointed out that regulations, licensing, a supply chain, as well as trust from society are required for the technology to happen on a large scale.

資料來源 : Offshore Energy